America's lack of complete success in Iraq is frustrating for all Americans. Although no one doubts that the American military forces are the most powerful in the world, there is also no doubt (anymore) that we are in a quagmire -- we can't seem to win or lose. Both a surge of troops and a withdrawal seem equally fraught with danger. The question dangles whether there was anything we could have learned from history that would have helped us.

Since the beginning of the Iraq War I have occasionally read articles that said something like “Many commentators have compared the Iraq War with Athens invasion of Sicily during the Peloponnesian War”. Maybe they have, but I did a Lexis search and I can’t find any writer that really discusses it. Every article just says that the comparison has been made by others and even that it has been done to death. Guess I'm reading the wrong things.

Some commentators have also mentioned Victor Davis Hanson’s recent “A War Like No Other,” in which the author considers the importance and novelty of the Peloponnesian War, as being, at least in part, a comparison of the ancient war with the current Iraq War. It must have been subliminal, because Hanson’s book doesn’t mention Iraq or America at all.

The truth is that there are some similarities between the two wars, and you can judge the significance of them yourself. Why write a blog on it? To some degree, if writers are going to keep saying there are similarities, someone should actually say what they are. But also, the Peloponnesian War was pretty interesting in its own right, and some of us can't talk about it enough.

Part I will consider the basics necessary to make any comparisons, and in a few weeks we will discuss the Athens/Sicilian War itself.

BACKDROP

The Peloponnesian War, really the second one, was fought in Greece, beginning a little over 2400 years ago in 431 B.C. and ending 27 long years later in 404 B.C. It was ostensibly between the two most powerful city-states, Sparta and Athens, but each was supported by many allied city-states.

PERSIA

Earlier that century, the Greeks, led by, Athens and Sparta, had fought off Persia, a huge and wealthy empire to the East. Persia is usually synonymous with modern day Iran, although at that time Persia’s empire stretched from now Western China across the expanse of Central Asia into parts of Europe and across Northern Africa. It was by far the largest and also the most powerful empire in the world.

There were also Greek colonies dotted along the perimeter of Asia, in what is now Turkey, and Persia had collected most of these into her empire. The Persian Emperor thought that he would just take over the Greek homeland too, and that it would be easy.

Most of us are aware, at least, that much of our heritage comes from Greece. Some small part comes from Persia as well. Many common words in the English language actually have, Persian roots, such as: magic and magi, checkmate (from “shahmat,” the king is dead) and chess, to name just a few. The Persian Empire at this time followed the religion of Zorastrianism which was a seed bed for many ideas that reached into Judiasm, Christianity and Islam.

THERMOPYLAE

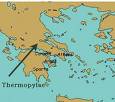

The invasion turned out differently than the great Persian king Xerxes hoped. One of the major battles took place at Marathon. The runner who hightailed it back home to give news of the Greek victory ran all 26 miles, giving us the name Marathon for the long distance race. Ten years later Persia invaded Greece again and was temporarily stopped at Thermopylae.

This was actually the name of a mountain pass which was extremely narrow. However, it was the only reasonable way for the Persians to get into Southern Greece by land, unless they wanted to go far out of the way.

This was actually the name of a mountain pass which was extremely narrow. However, it was the only reasonable way for the Persians to get into Southern Greece by land, unless they wanted to go far out of the way. There was Persia with its several hundred thousand troops. Greece was able to marshal only a few thousand soldiers. But the narrow pass was the perfect place for her unique type of warfare, as her flanks and rear could not be attacked. Protection at the pass led to a few advantages for the Greeks. One, they had developed much better armor and weaponry than the Persians. Two, they had perfected a technique called a phalanx,

where they would link arms and hold their long spears out in front of them.

where they would link arms and hold their long spears out in front of them. Somehow, the Greeks held off this army of hundred of thousands, but even with the added incentive of defending their own land, there was only so long they could do so.

Eventually, the Spartans volunteered to go it alone – just three hundred of them, while most of the others escaped (actually, probably up to a couple of thousand Greeks stayed, although 300 Spartans sounds so much better). The Persians had found a back way in with the help of a local. Virtually all of them died there, as they knew they would. The Persians moved on, but Thermopylae was a moral victory and a battle that has motivated soldiers throughout history. According to my English version of Herodotus' Histories, a monument later placed there included this inscription: "Go tell the Spartans, those who read/We took their orders, and now are dead". I have my doubts about how the writer from the 5th century B.C. knew how to rhyme in Greek which would be later translated into English still rhyming, but there you have it. Herodotus had a lot of doubts about the things he learned and told us too. I feel like I'm in good company.

SALAMIS

Soon after, the Athenians, the great Greek naval power, defeated the huge Persian navy at the battle of Salamis. Although not deemed as glorious a victory in history as Thermopylae, it was at least as important a victory. It was not the last battle either, but it cut off Persia's supply line by sea and may have been the most critical victory. After that, the Greeks were not seriously challenged by Persia in their own homeland, although many Greek colonies that were in what is now Turkey remained in the Persian Empire.

THE RIVALRY

The Greek city states were rarely united, and had this time come together only to defeat a foreign invader. They had language and some culture in common, but fought viciously among themselves. After defeating the Persians, the rivalry grew between Athens, which had entered its classical age in education, science, and the arts, and Sparta, a military state, dedicated to martial prowess. Athens had the best navy in Greece, and Sparta the best army. However, Sparta retreated within, leaving Athens with leadership of what was at first the Delian League and later became the Athenian Empire.

ATHENS

Over time, Athens, which had been experimenting with democracy for nearly two centuries, was influential in spreading this political practice sporadically throughout Greece. Athens did not act like a modern democracy, unless you believe the United States is presently an aggressive democracy enslaving the world and forcing its beliefs on everyone. Not only was Athens a slave power, as was just about everyone else, but it would use its military might or threats to force its political system on other Greek states. This allowed Sparta, which had enslaved its neighbors, to claim that the war was over freedom.

The goddess of wisdom and war was Athena, patron deity of Athens (although also worshipped in Sparta). Athens was famous for many things including architecture (such as the Parthenon), pottery, government, creating coinage, innovative theatre and philosophy. It is perhaps most famous for its long list of philosophers and artists who graced its walls, including philosophers Aristotle, Plato, Socrates, playwrites Euripides, Sophocles and Aristophanes and the political leader Pericles, to name only the most familiar. Athens is considered the mother of democracy and many other innovations in Western Civilization.

SPARTA

Sparta wasn’t exactly a monarchy, which indicates one ruler, because it, almost uniquely, had two Kings at a time. They weren’t all powerful rulers, though. A group of elders known as the Ephors also had a great deal of power. The Kings’ function was actually more military and religious in nature. To some degree Spartan citizens, as opposed to its slaves, had more freedom than Athenian citizens.

Young Spartans were raised to be warriors, being taken from their parents when infants to train. Spartans were Dorians who had invaded Greece centuries before. They had enslaved the local tribes, the Helots, when they settled on the peninsula, and were always worried that they would be attacked by the restless native population. It is one of the reasons that they preferred to remain close to home.The name Peloponnesian comes from the peninsula that Sparta was located on, supposedly named after the invading Dorian peoples' great ancestor, Pelops. Spartans could reach Athens in a matter of days through a thin isthmus (like so many English words, derived from the Greek) leading to the mainland.

Although Sparta was greatly feared for its military prowess, it soon became frightened of Athen’s growth. Both had many allies, splitting Greece into a jigsaw puzzle of two camps. Eventually Sparta invaded Athens in 460 B.C. This was the first Peloponnesian War. They finally entered into a truce about fifteen years later known as the Thirty Years Peace. It would not last 30 years.

THE START OF THE WAR

The truce made it about half way through its expected life. In 431 B.C., Sparta invaded Athens again and continued to do so for a number of years.

Although more powerful on land, Sparta could not get Athens to come out and fight. On Pericles’ advice, the Athenian population gathered within the Long Walls it had completed the peace, and remained there. Based upon the water’s edge, Athens’ powerful navy allowed it to continue to feed itself and trade. The idea was to use its navy to make hit and run attacks on the Peloponnesian peninsula. Athens' grain was farmed far to the North, outside of Sparta’s area of influence, and shipped directly to Athens’ protected port.

Having to settle for destroying farmlands and olive groves, Sparta ravaged the Athenian countryside. Being safe within walls had downside too. Not only were Athens’ crops destroyed, but the city inhabitants suffered two devastating plagues. But it won sea battles and kept its empire alive. Nevertheless, it also suffered virtually complete financial disaaster.

Finally, Athens succeeded in pinning a number of Spartan troops on an island (Sphacteria, if you care), and Sparta agreed to a truce for a while in order to save their lives. Ironically, Sparta sacrificed 300 lives at Thermopylae, including its great King Leonidas, without even a hope of stopping Persia there, but would not allow slightly more (about 420) to be captured or die in order to continue its still hopeful war with Athens.

SICILY

During this repose, Athens made a tragic mistake. Under the pretense of helping some neighboring democracies, it invaded the enormous island of Sicily in 414 B.C.

Even with its superior navy, Athens troops and sailors were virtually wiped out in the effort. The Sicilian defenders, with only a little help from a Spartan general, developed new marine techniques, improvising brilliantly to defeat the supposedly unconquerable Athenian navy. The loss wiped out Athenian finances, pride and seeming invincibility.

THE END OF THE WAR

Somehow, the war did not end there. Despite the devastating defeat, Athens lasted another ten years. Only with the help of numerous allies, including now the same Persian Empire Greece had defeated earlier, treason and some brilliant work by Spartan generals on land and sea, Sparta defeated Athens in the last major battle at Aigospotami (in modern day Turkish waters) where most of the Athenian fleet was destroyed. After 27 years, Athens surrender (404 B.C.) and Sparta finally tore down its "Long Walls".

Although Sparta now set an oppressive counsel to rule Athens ("The Thirty Tyrants"), it did not destroy it, as it might have. The war had been the most brutal the Greek world had been known, and it would have surprised no one if Sparta had put the Athenian men to the sword and taken the women as wives and slaves. Civilization would be different today had it done so.

When I was in high school we learned that Athens was able to defeat Sparta because it was a democracy and its citizens trained both mind and body, not just the body, as opposed to the militarily consumed Spartans. I have heard this repeated by a number of people my age, so obviously this teaching of "history" was quite prevalent, at least on Long Island, and I imagine elsewhere. I have to wonder in a country where most people still think that Saddam knocked down the Twin Towers, how many high school graduates (if they ever think about it at all) believe Sparta lost to Athens. A good question for one of those cultural polls.

LEGACY

Sparta’s victory did not do it much good. After a relatively brief hegemony, Sparta was left behind and eventually disappeared from history as a power or influence. Mostly we are left with the inspiring story of Thermopylae (about which I am advised a movie will be coming out this year), and the word “Spartan,” referring to a simple and hard lifestyle without luxuries or comforts. Athens, quickly regained much of its influence, and went on to historic greatness and legacy, if not much power. Even when Greece had been conquered the next century by Philip II of Macedonia (Alexander the Great’s father) and then by Rome a few centuries later, its conquerors left Athens, already revered for its contributions to culture, with its freedom.

Two weeks from now, we will revisit the Sicilian War we discussed briefly above and see how closely our present one mirrors it.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Your comments are welcome.